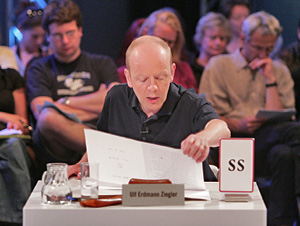

Ulf Erdmann Ziegler

Ulf Erdmann Ziegler was born in Neumünster in 1959 and lives in Frankfurt. Ziegler was suggested as Alain Claude Sulzer's competition sponsor.

Ulf Erdmann Ziegler was born in Neumünster in 1959 and lives in Frankfurt. Ziegler was suggested as Alain Claude Sulzer's competition sponsor.

Download text in:

Word file format (*.doc)

PDF file format (*.pdf)

Information on the author

Videoportrait

Ulf Erdmann Ziegler

Pomona

Kids loved 133 Pomona, probably because the television room hung over the garden, or even more probably because there were no rules for TV. And so they would flop onto a white flokati rug like a colony of seals on an ice floe, to watch Sesame Street and what followed it, which would lead to fights over which programme to watch. That split the group, the victorious ones in front of the television, peeved because they had been left on their own, the others in the garden, admiring the heron or sending smoke signals from the tree house. The Schullers wanted to prove that ‘children can find their own way in the media jungle. Perhaps better than we can,' as Petrus Schuller would say, something the other parents could certainly not countenance.

Hannelore Schuller didn't see any danger in the children watching the soppy chart songs and imitating the most wonderfully embarrassing scenes in the garden. She only had second thoughts when Marlen, who wasn't old enough for school yet, started to like Westerns, complicated fables of law and justice that ended with shoot-outs, so that with the window open 133 Pomona sounded like Bonanza. She couldn't really follow everything from her studio, but it surely wasn't a good sign that Marlen insisted she wasn't watching it all, only the beginning and the end, and then developed the habit of turning the sound off.

Occasionally Hannelore Schuller wondered, just to herself and rather rhetorically, how she had arrived here. We can answer that: in the Dauphine, over the Rheinknie Bridge from the medieval heart of Düsseldorf to Oberkassel, somehow getting lost in the port, heading straight for Neuß's city centre, guided by the minster, then out southwards and a little later the turn for the orchards, already largely divided into lots, partly still not cleared, partly already built on. That was the first time. Back to Düsseldorf, to a third floor flat in Unterbilk, not thinking any more of it for two apple-blossomings, or if at all, then with vague feelings of affection. Second excursion, Lore already with her sixth month pear silhouette, the following week the tenancy for 105 Pomona already signed, by both, Petrus Schuller, Hannelore Schuller, 20th August 1963 - their work colleagues had a good dig: Are you moving to an allotment, or what?, and their pale Dauphine swapped for a red Alfa, so that the people in the other slices of the terrace couldn't think they were one of them. That was half-true, as no one else in Pomona was ‘in advertising', and half-nonsense, because everyone with children borrows milk and butter from their neighbours.

In the night from the 22nd to 23rd November, already in labour and all around her whisperings about the fatal news from America, she was thrown into a new era, robbed of ease and the protecting bubble that had surrounded her. Petrus was blustering about scores having been settled with the ‘Catholic president' who the Puritan society hadn't been able to bear, as if he had forgotten that Lore converted for his sake. And in those days some of the Protestant worry about the world reverted to her, to her and to Johanna too, the baby with black eyes.

When she had met him, he had used hair-cream, a real quiff, man and boy at the same time. Petrus, at twenty-four, had been the youngest at Brad Kilip & Partners, taken on to oversee the application of the draft campaigns to varying magazine formats, within a year the right-hand man of Oberholtzer, Kilip's assistant; had come to know Hannelore Fleck and her portfolio in the main office, waylaid her and introduced her to Oberholtzer half an hour later, ‘Ober, look, this is Frau Fleck, she's got a deft hand.' Which she did.

Not that she, at twenty-two and a half, having graduated from Cologne's school of applied arts, was looking for a husband, but her life as Fräulein Fleck, lodging with a government employee's family in Kaiserswerth, no visitors after eight in the evening, if you please, was not what she had imagined as the Rhineland way of life. Petrus had two rooms in Unterbilk, not to be sniffed at, a little dark, but high-ceilinged, with stucco, radiogram, Bosch refrigerator, and a Biedermeier sofa - inherited --, and by the end of May 58 it happened, a few old-style beers in the old town, up and down along the bank of the Rhine in the Dauphine, long gazes from the driver's seat and back from the passenger seat. The evening was unforgettable, because the Biedermeier sofa collapsed halfway through, while in the next room a Chuck Berry 45 went round and round on the empty groove, crit-crit.

The Easter after Kennedy, they were among the Easter marchers, Lore in a blue and white striped skirt, like an inside-out Melitta cup, Johanna in a pre-war pram with giant, spoked wheels, Petrus in his ridiculous loafers with leather soles: never again (never again on an Easter march or never again with leather soles, that remained to be seen); for now ‘Never again war!' and ‘No to nuclear weapons!'. It turned out that out of two hundred participants, seven couples were from Pomona, easily recognisable by their prams and buggies. There were no grandmothers to keep an eye on the children in Pomona.

In the southern part of the Pomona development some of the orchards had been preserved, an enormous field, a hollow down towards the road, a main road admittedly, linked to Düsseldorf by the South Bridge. Petrus drove past it twice a day, going sixty in fourth gear, he was the only one from there who did. The plots in the hollow were definitely the best, facing away from the development and not expensive, certainly not in comparison with Düsseldorf; but the noise. So Petrus, on the Easter March of 65, wearing Hush Puppies (with crepe soles), joined the little group of Pomos who spent hours discussing plans, asking the development's architects, phoning the relevant bodies, before finally, on 1st August 1967, proposing to the town of Neuß the construction of an earth wall, to make a ‘peaceful life in the country' possible again, as had once been promised. Sensing an impending debacle, the developers had started to make concessions. With the momentum of their own activity, the Schullers bought 133 Pomona, one of the biggest plots of all of them, and paid for it, as Oberholtzer said in astonishment, ‘from the petty cash'. Indeed they had saved enough money by then. It was even enough to keep the Alfa and buy a brand-new Volkswagen estate in bright orange to join it. Which, however, made enough noise for two cars.

Hannelore Fleck had a bright and sensitive face which was easy to read, gloom could be recognised in a welling up in her eyes, joy as they became smaller, crystalline, grey-blue marbles, making it hard to look away. Petrus Schuller's features were leathery and severe then, his dark brows almost met in the middle, his mouth more silvery than red, something belonging to a marine species, that you could find and open; a scornful feature that could flip over into a hedonistic grin. She was clever enough not to say anything against Elvis, because that hardens a man's heart and softens his stick; she went for the opposite. Barely had they started and she realised that it wouldn't be easy. He was eloquent on trivialities and silent on important issues. The ease of the first few weeks, always close to the grotesque due to contraceptive measures, was her own, something that came from her family, a present to him, and that he took as if it were not. And that is always how couples are formed, as we know. She had soon learnt the steps that older people deciphered as an unleashing of base urges; the polka just wasn't her thing. Petrus was in awe of what the dances did to the girls' faces, their open mouths, the way their eyes went weak, something fantastical that had no equivalent in reality, the fearful Catholics with their notorious light out, come hither promise, but as if it were a compromise. Hannelore the opposite, her dancing technique great, but her nakedness electric, no limits, showing how much she liked it. And then the surprise, when dancing in pairs suddenly became old-fashioned and the music became blacker, more laid-back, brass added. That suited her, the mixture of folding and boxing - or how else would you describe it? -, still sporting a ponytail and yet already in a different era.

Johanna had climbed out of their pre-war pram with serious determination, a child of terrifying calm, who Petrus carried on his shoulders like a trophy, the spitting image of his Latin physiognomy. Marlen was born almost bald and became a blond child, so that could have been the end, call it a draw. Both were new to Lore, the pill and the pope. Maybe Pomona was the deciding factor, its rhythm of apple blossom and fruit, the impression that children just rolled out of front gardens and into the roads, almost impossible to keep track of them. In any case, Marlen was not a year old when Lore become pregnant again; so Cristina was what in show business you call the encore, the familiar song, saved for last and laid in a gently polished version at the feet of the breathless audience.

Johanna had learnt to walk early, to keep track of things. To the surprise of the Pomos she cried silent tears. She gave up her wooden highchair without a fight to Marlen, who screamed her head off when she was to be dethroned by Cristina, so that Petrus was forced to bring a second one from Düsseldorf; the two of them sat opposite each other like a queen in her mirror. Johanna was only three and fed Cristina like a nanny; she was reading fluently at four; and if in the summer of 1969 at the age of six she had been asked to supervise the building of 133 Pomona, she wouldn't have been unhappy, a soldier for the family, the street and the development itself. At sixteen she would mount a horse and singlehandedly rout an enemy people, it just remained to be seen which one.

Perhaps it was the proud heritage of the town having been founded by the Romans - unsuccessfully besieged! -, that made the town council unwilling to see that on the edge of Pomona, of all places, a wall needed to be raised, to protect from cars. The Pomos offered to undertake the survey and construction work themselves and even wanted to pay for it, which didn't please the relevant bodies one little bit, where would it lead to, were they to hand over to the common people the construction of the town's fortifications. First of all the town council, of what had once been Novaesium and Nussia, then Nuys and Neus, decided to abolish ‘Neuß', and instead in ‘the interests of a unified orthography' to call the town ‘Neuss' from now on. That was on 21st November 1968, so that we would never be able to claim that the era's revolutions passed the fortress on the left of the Rhine by. Did Pomona actually belong to the Nuys fortress - wasn't it rather a sorry appendage to a future motorway system, and shouldn't its rebellious inhabitants have appealed to the highways agency? And wasn't the district, which Neuss had ballooned to become, not made up largely of developments enclosed by motorways and trunk roads, so that Neuss, if Pomona's case set a precedent, would become a union of mini-fortresses, sand castles, as it were? It was 1969 and, as regrettable as it was, they really couldn't do anything right then: there were elections coming up.

There are two ways to look at a situation like this. Either you see that there is no sign of a solution. Or you come to the conclusion that there is no way back, to doing nothing, and that the authorities would soon be forced to act against their own will. That is how Petrus Schuller thought, which is typical of advertising people, able to interpret the abstract space that opens up between a step backwards and progress, and so to turn the wheel of history, certainly to their own advantage. He brought an architect with him from Düsseldorf who, being six and a half foot tall, pushed the Alfa's passenger seat back all the way, so that Oberholtzer, who had recommended the architect and whose curiosity had brought him along, spoke to Petrus via the rearview mirror as they drove over the Rhine, nothing important, nothing that Petrus will remember more than the fact that someone from the agency came to Pomona too; and it was certainly the right moment, for a plot with apple trees in the height of summer is far more impressive than the life of a family of five in a terraced house.

‘Quite something,' said Ober, after he had massaged his knee through his creased trousers. As the plot didn't have a fence you had to work out first of all where it actually ended.

As if it didn't affect his interests in the least, the architect mooted, ‘If yer little wall don't come, yer screwed.' Said before Lore joined them.

133 Pomona was on a cul-de-sac, on the left of which were three plots, sloping down a little. The first bordered the road in the development, the last one - the open land where the wall was to be built, and the middle one Petrus presented as his own. It lay in a block of six plots in all, the other three were on a parallel drive.

‘So, that's three boundaries, but five compost heaps, not including yers,' summarised the architect.

Petrus understood him. ‘We didn't want to be right at the front, that would have been the biggest one. The one in the hollow is too small. This one's a square. That gives us more freedom.' He plucked weeds from one of the grey-white stone blocks that marked the southeast corner.

‘I'd close it up like a castle,' said Ober.

‘Once round with an atrium, but there ain't more in it than that,' countered the architect. ‘So what height's allowed in yer planning permission?'

Petrus: ‘Nine and a bit. A classical gabled roof, if wanted.'

Architect: ‘Could be done without.'

Ober: ‘It doesn't have to be the Villa Savoye.'

Architect: ‘Why not?'

The way from 105 to 133 was only four minutes by foot, but it had something about it of a return to paradise. First the street in front of the terraced houses, kitchen by kitchen, toilet next to toilet, then the intermediate buildings, greyish red brick houses surrounded by dozing gardens, and then, beyond the development's southern street - that like every other street in Pomona was also called Pomona, who thought that one up - the remains of the apple orchards, scarcely noticeable beyond its blossom and fruit, just like Lore herself. Petrus was not the kind of ‘give me twelve children even if you die in the process' Catholic whose wireless was set to Radio Rome, not that, but he had still pressured her into coming off the pill. It would be so good to have a boy too, and then, when her period didn't come, three weeks overdue, he had gently shifted his position and insisted that he would be just as happy to have a girl. In the autumn of 67 she had returned, after Cristina, to work in the agency, trousers instead of skirt, her hair chin-length, four weeks' confusion about the new spray technique until she had it sussed, illustrations had to shine like cars' bonnets now.

She bumped into the threesome at the other end of Pomona. The architect had calculated that fifteen percent of the trees could be left. Garden facing south, obviously. On a little notebook that carried a brewery's logo, he had sketched a two storey building with a flat roof, partially supported on columns. A Welcome! to Frau Schuller, who in turn was surprised at Ober's presence. They stood somewhere near the middle of the plot's southern boundary and pointed to an imaginary house: the front to the west, the raised service section north-south beside the cul-de-sac, the drive to the backyard or garden down there, the living quarters on the ground floor like a crossbeam, east to west, and partly upstairs too, depending on the number of children, and in any case, because of the skylight, the studio to be upstairs.

‘What studio?' asked Lore.

‘Yers, lady,' said the architect.

That very autumn the building land was tested, the plot surveyed, the trees felled and their roots excavated, and before the frosts came, the cellar was finished. Johanna had an enormous gash on St Nicholas' Day from a fall, although the children hadn't been allowed to play on the building site. ‘Or just because of that,' said Petrus, ‘perhaps we should have shown them how to play there.' His gift for seeing the inevitable approaching: in March the town of Neuss arrives with three diggers and starts to pile up rubble, tipped from articulated lorries, into a defensive wall. And so the town and the Schullers are in a race, the Schullers finish first, they move on 1st November 1970, the following February the town is still building the wall. Pomona's southern edge looks like a lunar landscape. Lore knows that she can't go mad now. She hasn't accepted the word ‘studio', she calls it a workroom. But it is large, well-lit, clean, with a Marabu drawing table under the skylight. ‘It's my invention,' joked Ober at the house-warming party. And there was some truth in that. Ober had discovered how to avoid the forever boomeranging return of the married illustrator to a hectically expanding company. ‘There will always be work, no fear there,' Petrus said, but she was afraid, that Petrus would bring the work and take her sketches - and she would only see what she herself had come up with. A drop runs down the copper kettle . . . a tear. An occupational hazard.

133 Pomona belongs to the children. Lore wonders if it is better to control your life or to go with the flow. She sketches a revue act on a pad, the phalanx of chorus-girls, as question marks on the left and as exclamation marks on the right. Her girls even accepted Fabian as a toy, they can barely wait to bathe him, to change his nappies and to rock him to sleep. All the small fry from the terraced houses also over too, for as long as they can; luckily they have times to be in by. Johanna is always the leader, whether there are fifteen children or four. While Marlen withdraws. Maybe she's only pretending with the Westerns. Lore sits down in the empty television room when one of these series is on, unintelligible stuff, particularly without the sound. She doesn't change a thing. Marlen is a little startled when she returns, she's scared of her own mother, or feels she's been caught in the act, but covers it up, her mouth open, her eyes on the floor. She sprawls out on the flokati. A reconciliation scene for the family, over-acted. The ranch in the evening light. And suddenly Marlen is sitting there, her legs drawn up and her arms wrapped around them, her head on her knees like an amphora. She doesn't move. The credits are running onscreen: title, actors, production company, the script as if painted by hand, jagged, flickering, white on black. Marlen is six and a half. In the moment when the presenter appears she lets her arms fall, rolls onto her back and to the side, looks her mother in the eyes and whispers entranced,

‘It's always exactly the same. Absolutely exactly the same.'

Translated by Stefan Tobler